An Alcoholic Family Is One in Which ________.

Temperance Lecture by Edward Edmondson, Jr., Dayton Art Institute, 1861

Alcoholism in family systems refers to the conditions in families that enable alcoholism, and the effects of alcoholic beliefs by ane or more than family members on the remainder of the family. Mental wellness professionals are increasingly considering alcoholism and addiction as diseases that flourish in and are enabled by family unit systems.[one]

Family members react to the alcoholic with detail behavioral patterns. They may enable the addiction to go along past shielding the addict from the negative consequences of their actions. Such behaviors are referred to as codependence. In this manner, the alcoholic is said to endure from the disease of addiction, whereas the family members suffer from the illness of codependence.[2] [3] While it is recognized that habit is a family unit disease, affecting the unabridged family system, "the family is often ignored and neglected in the treatment of addictive illness."[iv] Each private member is affected and should receive treatment for their own do good and healing, simply in add-on to benefitting the individuals themselves, this also helps to better support the addict/alcoholic in his/her recovery process. "The chances of recovery are profoundly reduced unless the co-dependents are willing to accept their role in the addictive process and submit to treatment themselves."[5] "Co-dependents are mutually dependent on the addict to fulfill some need of their ain."[4]

For example, the "Master Enabler" (the primary enabler in the family) will often turn a bullheaded eye to the addict's drug/alcohol utilise every bit this allows for the enabler to continue to play the victim and/or martyr role, while allowing the addict to keep his/her own destructive beliefs. Therefore, "the behavior of each reinforces and maintains the other, while as well raising the costs and emotional consequences for both."[6]

Alcoholism is one of the leading causes of a dysfunctional family.[vii] "Nearly one-quaternary of the U.S. population is a member of family unit that is afflicted by an addictive disorder in a first-degree relative."[iv] [viii] Equally of 2001, there were an estimated 26.eight 1000000 children of alcoholics (COAs) in the U.s.a., with equally many as 11 million of them under the historic period of 18.[9] Children of addicts have an increased suicide rate and on average accept total health care costs 32 percent greater than children of nonalcoholic families.[9] [10]

According to the American Psychiatric Clan, physicians stated three criteria to diagnose this disease: (ane) physiological bug, such every bit hand tremors and blackouts, (2) psychological problems, such equally excessive desire to drink, and (3) behavioral problems that disrupt social interaction or work performance.[11]

Adults from alcoholic families feel higher levels of state and trait anxiety and lower levels of differentiation of cocky than adults raised in not-alcoholic families.[12] Additionally, adult children of alcoholics have lower self-esteem, excessive feelings of responsibility, difficulties reaching out, higher incidence of depression, and increased likelihood of becoming alcoholics.[xiii]

Parental alcoholism may affect the fetus fifty-fifty before a child is built-in. In pregnant women, alcohol is carried to all of the mother's organs and tissues, including the placenta, where information technology easily crosses through the membrane separating the maternal and fetal blood systems. When a pregnant adult female drinks an alcoholic potable, the concentration of alcohol in her unborn baby's bloodstream is the same level as her own. A significant adult female who consumes booze during her pregnancy may give birth to a babe with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS).[11] FAS is known to produce children with damage to the central nervous system, full general growth and facial features. The prevalence of this grade of disorder is thought to be between 2–5 per 1000.[xiv]

Alcoholism does not have compatible effects on all families. The levels of dysfunction and resiliency of the non-alcoholic adults are important factors in effects on children in the family. Children of untreated alcoholics score lower on measures of family unit cohesion, intellectual-cultural orientation, active-recreational orientation, and independence. They have higher levels of disharmonize inside the family, and many feel other family unit members every bit distant and non-communicative. In families with untreated alcoholics, the cumulative effect of the family unit dysfunction may affect the children's ability to grow in developmentally healthy means.[15] [16]

Family roles [edit]

"A maniacal man is visited in prison past his children, all ruined through his drinking addiction". Reproduction of an etching by 1000. Cruikshank, 1847.

The role of the "Chief Enabler" is typically the spouse, pregnant other, parent, or eldest child of the alcoholic/addict. This person demonstrates "a strong trend to avoid whatsoever confrontation of the addictive behavior and a subconscious effort to actively perpetuate the habit."[4] The "Principal Enabler" also often doubles every bit the "Responsible One",[vi] or "Family Hero"[half dozen] some other role causeless by family members of the alcoholic/aficionado. Both the "Main Enabler" and "Responsible I" (aka "Model Child"[4]) will take "over [the alcoholic/addict's] roles and responsibilities".[4] For example, a parent might pay for expenses and take over responsibilities (i.e. car payments, the raising of a grandchild, provide room and board, etc.), while a kid may provide care for their siblings, become the "peace keeper" in the domicile, accept on all the chores and cooking, etc. A spouse or pregnant other may overcompensate by providing all the care to the children, being the sole financial correspondent to the household, covering up or hiding the habit from others, etc. This role ofttimes receives the most praise from not-family members, causing the individual to struggle to see that it is an unhealthy role which contributes to the addict/alcoholic'south illness as well equally the family'southward dysfunction.

Another role is that of the "Problem Child" or "Scapegoat."[four] [6] This person "may be the just [one] clearly seen as having a trouble"[vi] outside of the bodily addict/alcoholic. This kid (or developed child of the alcoholic(south)) "gets blamed for everything; they have bug at school, exhibit negative beliefs, and oftentimes develop drug or alcohol bug every bit a way to human activity out. Their beliefs demands whatever attending is bachelor from parents and siblings."[4] This often "takes the focus off the parental booze problem", and the child tin can be the "scapegoat" nether the myth that his/her behavior fuels the parent's drinking/using.[6] However, this child draws attending from outsiders, which may contribute to the recognition of the family alcohol problem by outsiders.[vi]

The "Lost Kid" role is identified in this system through children that are "withdrawn, 'spaced-out,' and disconnected from the life and emotions around them."[iv] They often avert "any emotionally confronting issues, [and and so are] unable to course close friendships or intimate bonds with others."[four]

Other children "trivialize things by minimizing all serious issues as an avoidance strategy [and] are well liked and easy to befriend but are usually superficial in all relationships, including those with their own family unit members."[4] These children are known as the "Mascot" or "Family Clown".[4]

Still, alcoholic family unit roles have not withstood the standards that psychological theories of personality are typically subjected to. The evidence for alcoholic family unit roles theory provides limited or no construct validity or clinical utility.[17]

Prevalence [edit]

Based on the number of children with parents meeting the DSM-V criteria for alcohol corruption or alcohol dependence, in 1996 there were an estimated 26.8 million children of alcoholics (COAs) in the United States of which 11 1000000 were under the age of 18.[18] As of 1988, it was estimated that 76 million Americans, nearly 43 percent of the U.S. adult population, have been exposed to alcoholism or problem drinking in the family, either having grown upwards with an alcoholic, having an alcoholic blood relative, or marrying an alcoholic.[19] While growing up, nearly one in five developed Americans (18 percent) lived with an alcoholic. In 1992, information technology was estimated that one in eight adult American drinkers were alcoholics or experienced problems as consequences of their alcohol use.[twenty]

Familiality [edit]

Children of alcoholics (COAs) are more susceptible to alcoholism and other drug corruption than children of not-alcoholics. Children of alcoholics are iv times more likely than non-COAs to develop alcoholism. Both genetic and environmental factors influence the development of alcoholism in COAs.[xvi] [21]

COAs' perceptions of their parents drinking habits influence their own future drinking patterns and are developed at an early age. Booze-related expectancies are correlated with parental alcoholism and alcohol abuse amidst their offspring.[22] [23] Trouble-solving discussions in families with an alcoholic parent contained more negative family interactions than in families with non-alcoholic parents.[21] [22] Several factors related to parental alcoholism influence COA substance corruption, including stress, negative impact and decreased parental monitoring. Impaired parental monitoring and negative touch on correlate with COAs associating with peers that support drug use.[22]

After drinking alcohol, sons of alcoholics feel more of the physiological changes associated with pleasurable furnishings compared with sons of non-alcoholics, although only immediately subsequently drinking.[24]

Compared with not-alcoholic families, alcoholic families demonstrate poorer problem-solving abilities, both among the parents and within the family unit as a whole. These communication bug many contribute to the escalation of conflicts in alcoholic families. COAs are more likely than not-COAs to be aggressive, impulsive, and engage in disruptive and sensation seeking behaviors.[22] [25]

Alcohol addiction is a complex disease that results from a variety of genetic, social, and environmental influences. Alcoholism afflicted approximately four.65 percentage of the U.S. population in 2001–2002, producing severe economic, social, and medical ramifications (Grant 2004). Researchers guess that between 50 and 60 percent of alcoholism risk is determined past genetics (Goldman and Bergen 1998; McGue 1999).This strong genetic component has sparked numerous linkage and association studies investigating the roles of chromosomal regions and genetic variants in determining alcoholism susceptibility.

Marital relationships [edit]

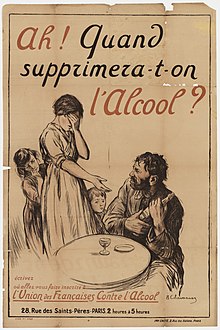

A French temperance organization poster depicting the effects of alcoholism in a marriage

Alcoholism ordinarily has potent negative effects on marital relationships. Separated and divorced men and women were three times as probable equally married men and women to say they had been married to an alcoholic or problem drinker. Virtually two-thirds of separated and divorced women, and almost half of separated or divorced men under historic period 46 accept been exposed to alcoholism in the family unit at some time.[19]

Exposure was higher among women (46.2 per centum) than amid men (38.9 percent) and declined with age. Exposure to alcoholism in the family was strongly related to marital status, independent of age: 55.five percentage of separated or divorced adults had been exposed to alcoholism in some family member, compared with 43.five per centum of married, 38.5 percent of never married, and 35.5 pct of widowed persons. Nearly 38 percent of separated or divorced women had been married to an alcoholic, but merely near 12 percentage of currently married women were married to an alcoholic.[19]

Children [edit]

Prevalence of abuse [edit]

Over one million children yearly are confirmed equally victims of child abuse and neglect by state child protective service agencies. Substance abuse is 1 of the two largest issues affecting families in the United States, beingness a factor in well-nigh four-fifths of reported cases. Alcoholism is more prevalent amid child abusing parents. Alcoholism is more strongly correlated to kid abuse than depression and other disorders.[26] [27]

Adoption plays only a slight office in alcoholism in the family. Studies were washed comparison children who were born into a family with an alcoholic parent and raised by adoptive (non-alcoholic) parents as compared to children built-in to not-alcoholic parents and raised by adopted alcoholic parents. The results (in US and Scandinavian studies) were that those adopted children born of an alcoholic parent (and adopted past non-alcoholic parents ) developed alcoholism at college rates as adults.[28]

Correlates [edit]

Children of alcoholics exhibit symptoms of depression and anxiety more than than children of non-alcoholics. COAs have lower self-esteem than non-COAs from babyhood through young adulthood.[21] [29] Children of alcoholics evidence more symptoms of anxiety, depression, and externalizing behavior disorders than not-COAs. Some of these symptoms include crying, lack of friends, fright of going to school, nightmares, perfectionism, hoarding, and excessive self-consciousness.[xxx]

Many children of alcoholics score lower on tests measuring cerebral and verbal skills than not-COAs. Lacking requisite skills to express themselves tin can impact academic performance, relationships, and chore interviews. The lack of these skills exercise non, still, imply that COAs are intellectually impaired.[31] [32] COAs are also shown to take difficulty with abstraction and conceptual reasoning, both of which play an of import part in problem-solving academically and otherwise.[33] [34]

In her volume Developed Children of Alcoholics, Janet G. Woititz describes numerous traits common amid adults who had an alcoholic parent. Although not necessarily universal or comprehensive, these traits constitute an adult children of alcoholics syndrome (cf. the piece of work of Wayne Kritsberg).

Coping Mechanism [edit]

Suggested practices to mitigate the impact of parental alcoholism on the evolution of their children include:[35]

- Maintaining salubrious family traditions and practices, such every bit vacations, mealtimes, and holidays

- Encouraging COAs to develop consistent, stable, relationships with significant others outside of the family unit.

- Planning non-drinking activities to compete with alcoholic behaviour and tendencies.[36]

Resilience [edit]

Professor and psychiatric Dieter J. Meyerhoff state that the negative effects of alcohol on the body and on health are undeniable, just individuals should not forget the almost important unit in society that this is affects the family and the children. The family is the main institution in which the child should experience safe and have moral values. If a good starting point is given, information technology is less likely that when a child becomes an adult, has a mental disorder or is addicted to drugs or alcohol.[37] Co-ordinate to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) children are in a unique position when their parents abuse booze. The behavior of a parent is the essence of the problem, considering such children do not take and do not receive support from their own family. Seeing changes from happy to aroused parents, the children begin to call back that they are the reason for these changes. Self-accusation, guilt, frustration, anger arises because the child is trying to understand why this behavior is occurs.[38] Dependence on alcohol has a huge harm in childhood and adolescent psychology in a family unit environment. Psychologists Michelle L. Kelley and Keith Klostermann describe the effects of parental alcoholism on children, and describe the development and behavior of these children. Alcoholic children often face problems such as behavioral disorders, oppression, law-breaking and attention deficit disorder, and there is a higher risk of internal beliefs, such equally depression and anxiety. Therefore, they are drinking earlier, drinking alcohol more oft and are more likely to grow from moderate to severe alcohol consumption. Young people with parental abuse and parental violence are probable to live in large crime areas, which may have a negative bear on on the quality of schools and increase the affect of violence in the expanse. Paternity alcoholism and the general parental verbal and physical spirit of violence witnessed the fears of children and the internalization of symptoms, greater likelihood of child aggression and emotional misconduct.[39]

Research on alcoholism within families has leaned towards exploring bug that are wrong in the community rather than potential strengths or positives.[xl] When researchers conduct enquiry that helps communities, it can be easier for customs members to identify with the positives and work towards a path of resilience. Flawed research blueprint in developed children of alcoholics (ACOA) research showed ACOAs were psychologically damaged.[41] Some flawed research designs include using ACOAs equally part of the command group and comparing them to other ACOAs within the same study. This may accept caused some limitations in the report that were not listed. When comparison ACOAs to other ACOAs, it is difficult to translate accurate results that testify certain behaviors in the group studied. Research that has been conducted more recently has used command groups with non-ACOAs to see whether the behaviors align with prior enquiry. This research has shown that behaviors were similar between not-ACOAs and ACOAs. An eighteen-year-long study compared children of alcoholics (COA) to other COAs. In failing to utilise not-COAs equally controls, we miss an opportunity to see if the negative aspects of a person are related to having an alcoholic parent, or are they but but a fact of life.[42] For case, in Werner'due south study, he found that 30 percentage of COAs were committing serious delinquencies.[42] This data would have been more usable if they had viewed the percentage of those committing crimes when compared to not-ACOAs. In a study conducted in a midwestern university, researchers found that there was no pregnant difference between ACOA and non-ACOA students. Ane of the main differences was the student'due south views on how they connect their past experiences with their current social-emotional functioning. Students who were ACOAs did non demonstrate problems with their perspective on their interpersonal issues whatever more than the non-ACA students. However, this report did show that at that place were other underlying problems in the family structure that may attribute to the perception of non being well adjusted in life.

Due to the flawed research that has been conducted in the by, many stereotypes have followed ACOAs.[43] ACOAs take been identified as having a diverseness of emotional and behavioral problems, such as slumber problems, assailment and lowered self-esteem.[43] When it comes to being a COA or ACOA, there is still promise. Results showed that a supportive and loving relationship with one of the parents can counterbalance the possible negative effects of the relationship with the alcoholic parent. When there is one alcoholic parent in the household, it helps if the child relies on other family members for support. It may exist the 2d parent, siblings or members of the extended family. Having other supportive family members can help the child feel like s/he is not lone.[44] Younger generations of ACOAs scored more positively, in terms of coping mechanisms. This may exist due to fact that alcoholism is seen more than equally an illness nowadays, rather than a moral defect. There has been less victim blaming of alcoholism on parent'south, considering information technology has at present been declared a affliction rather than a behavioral problem.[41] Studies prove that when ACOAs utilize positive coping mechanisms, it is related to more than positive results. When an ACOA approaches their bug, rather than avoids them, it often relates to having a positive outlook.[41] Studies take shown that ACOAs and COAs have more compulsive behaviors that may cause the need for higher achievement.[45] Some ACOAs have shown that the only style to survive is to fend for themselves. This causes a sense of independence that helps them become more self-reliant. Because they perceive that independence and difficult work as necessary, ACOAs develop a sense of survival instinct.[46]

Implications for Counselors [edit]

Counselors serving ACOAs need to be careful to non presume that the client's presenting problems are due solely to the parent's alcoholism. Exploring the ACOAs life events, such as the number of alcoholic parents, length of time the client lived with the alcoholic parent, past interventions, and the office of extended family unit may help in determining what the correct method of intervention may exist.[43]

Many factors tin can affect marital and/or parenting difficulties, merely in that location has not been whatsoever evidence found that tin link these issues specifically to ACOAs.[45] Research has been conducted to endeavour to identify issues that arise when someone is a COA. It has been hard to isolate these bug solely to the fact that the child's parents are alcoholics. Other behaviors need to exist studied, like dysfunctional family relationships, childhood abuse and other childhood stressors and how they may contribute to things similar low, feet and bad relationships in ACOAs.[45]

Counselors serving ACOAs can also assist by working on building coping mechanisms such as creating meaningful relationships with other non-alcoholic family members. Having other family unit members who are supportive tin help the ACOA feel similar they are non alone.[44] Counselors can also provide some psycho-educational activity on alcoholism and its effects on family members of alcoholics. Enquiry shows that ACOAs experience less similar blaming their parents for their alcoholism after learning that alcoholism is a disease, rather than a behavior.[41]

Pregnancy [edit]

Prenatal booze-related effects can occur with moderate levels of alcohol consumption past non-alcoholic and alcoholic women. Cerebral operation in infants and children is not equally impacted past mothers who stopped booze consumption early on in pregnancy, even if it was resumed after giving birth.[47]

An analysis of six-yr-olds with alcohol exposure during the second-trimester of pregnancy showed lower academic functioning and problems with reading, spelling, and mathematical skills. Half-dozen percent of offspring from alcoholic mothers have fetal booze syndrome (FAS). The risk an offspring born to an alcoholic mothers having FAS increases from vi per centum to 70 percent if the mother's previous child had FAS.[48]

People diagnosed with FAS have IQs ranging from 20–105 (with a mean of 68), and demonstrate poor concentration and attention skills. FAS causes growth deficits, morphological abnormalities, mental retardation, and behavioral difficulties. Among adolescents and adults, those with FAS are more than likely to have mental wellness problems, dropping out or be suspended from schools, problems with the police force, require assisted living equally an adult, and problems with maintaining employment.[48]

Come across also [edit]

- Developed Children of Alcoholics

- Al-Anon/Alateen

- Concordance (genetics)

- Dual diagnosis

- Dysfunctional family

- Nar-Anon

- National Association for Children of Alcoholics

- Self-medication

References [edit]

- ^ Crnkovic, A. Elaine; DelCampo, Robert L. (March 1998). "A Systems Approach to the Treatment of Chemical Habit". Contemporary Family Therapy. xx (1): 25–36. doi:10.1023/A:1025084516633. ISSN 1573-3335. S2CID 141085303.

- ^ O'Farrell, Timothy J; Fals-Stewart, William (2006). "An Introduction to Behavioral Couples Therapy for Alcoholism". Behavioral Couples Therapy for Alcoholism And Drug Abuse. Guilford Printing. pp. 1–7. ISBN978-one-59385-324-ii. OCLC 64336035.

- ^ Cermak, TL (1989). "Al-Anon and recovery". Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Vol. 7. pp. 91–104. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-1678-5_5. ISBN978-i-4899-1680-viii. ISSN 0738-422X. PMID 2648500.

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j chiliad 50 Inaba, Darryl (2011). Uppers, downers, all arounders : physical and mental effects of psychoactive drugs. Cohen, William Eastward., 1941– (seventh ed.). Ashland, Or.: CNS Publications. ISBN9780926544307. OCLC 747281783.

- ^ (Gorski, 1993; Liepman, Keller, Botelho, et al., 1998)

- ^ a b c d east f g Kinney, Jean (2012). Loosening the grip : a handbook of alcohol information (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN9780073404684. OCLC 696942382.

- ^ Barnett, Mary Ann (October 2003). "All in the Family: Resources and Referrals for Alcoholism". Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 15 (x): 467–472. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2003.tb00333.x. ISSN 1745-7599. PMID 14606136. S2CID 40389156.

- ^ (Liepman, Parran, Farkas, et al., 2009)

- ^ a b Mulligan, Kate (5 October 2001). "Al-Anon Celebration Spotlights Importance of Family Interest". Psychiatric News. 36 (9): 7. doi:ten.1176/pn.36.19.0007.

- ^ Drake, Robert E.; Racusin, Robert J.; Tater, Timothy A. (1 August 1990). "Suicide Amidst Adolescents With Mentally Ill Parents". Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 41 (8): 921–922. doi:10.1176/ps.41.8.921. ISSN 0022-1597. PMID 2401483.

- ^ a b Parsons, Tetyana (14 December 2003). "Alcoholism and Its Effect on the Family". AllPsych . Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Maynard, Stuart (1999). "Growing upwards in an alcoholic family system: the event on anxiety and differentiation of self". Journal of Substance Abuse. 9: 161–170. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(97)90014-half dozen. ISSN 0740-5472. PMID 9494947.

- ^ Cutter, CG; Cutter, HS (January 1987). "Feel and modify in Al-Anon family groups: adult children of alcoholics". Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 48 (1): 29–32. doi:10.15288/jsa.1987.48.29. ISSN 0096-882X. PMID 3821116.

- ^ Paley, Blair; O'Connor, Mary J. (three September 2009). "Intervention for individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Treatment approaches and instance management". Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 15 (three): 258–267. doi:x.1002/ddrr.67. PMID 19731383.

- ^ Moos, R.H.; Billinop, A.B. (1982). "Children of alcoholics during the recovery process: Alcoholic and matched command families". Addictive Behaviors. 7 (2): 115–164. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(82)90040-5. PMID 7102446.

- ^ a b Windle, Michael (1997). "Concepts and Problems in COA Inquiry" (PDF). Alcohol Health and Research World. 21 (3): 185–191. PMC6826804. PMID 15706767. Archived (PDF) from the original on xv November 2010.

- ^ Vernig, Peter (2010). "Family unit Roles in Homes With Alcohol-Dependent Parents: An Show-Based Review". Substance Apply & Misuse. 46 (4): 535–542. doi:10.3109/10826084.2010.501676. PMID 20735193. S2CID 3279171.

- ^ Eigen, 50.; Rowden, D. (1996). "Department 1: Enquiry - A Methodology and Current Approximate of the Number of Children of Alcoholics in the United States". In Abbott, Stephanie (ed.). Children of Alcoholics: Selected Readings (Volume 2 ed.). Rockville, MD: National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACoA). pp. 1–22. ISBN978-0-9645327-4-eight.

- ^ a b c Schoenborn, CA (September 1991). "Exposure to Alcoholism in the Family: United States, 1988". Advance Data from Vital and Wellness Statistics. 30 (205): 1–xiii. ISSN 0147-3956. PMID 10114780.

- ^ Hardwood, H; Fountain, D.; Livermore (1998). The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse in the United States, 1992 (Written report). Rockville, MD: DHHS, NIH, NIDA, OSPC, NIAAA, OPA. NIH Publication No. 98-4327. Archived from the original on fifteen Nov 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

Analysis by the Lewin Group

- ^ a b c Ellis, Deborah, A.; Zucker, Robert A.; Fitzgerald, Hiram Due east. (1997). "The Role of Family Influences in Development and Risk" (PDF). Alcohol Wellness and Research World. 21 (3): 218–225. ISSN 0090-838X. PMC6826803. PMID 15706772. Archived (PDF) from the original on fifteen Nov 2010.

- ^ a b c d Jacob, Theodore; Johnson, Sheri (1997). "Parenting Influences on the Development of Alcohol Abuse and Dependence" (PDF). Alcohol Wellness and Inquiry World. 21 (three): 204–209. ISSN 0090-838X. PMC6826805. PMID 15706770. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 Nov 2010.

- ^ Zucker, Robert A.; Kincaid, Stephen B.; Fitzgerald, Hiram E.; Bingham, Raymond (August 1995). "Booze Schema Acquisition in Preschoolers: Differences Between Children of Alcoholics and Children of Nonalcoholics" (PDF). Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. nineteen (4): 1011–1017. doi:ten.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00982.ten. hdl:2027.42/65209. ISSN 1530-0277. PMID 7485810.

- ^ Finn, Peter, R.; Justus, Alicia (1997). "Physiological Responses in Sons of Alcoholics" (PDF). Alcohol Health and Research Globe. 21 (3): 227–231. ISSN 0090-838X. PMC6826811. PMID 15706773. Archived from the original (PDF) on fifteen November 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ Sher, Kenneth, J. (1997). "Psychological Characteristics of Children of Alcoholics" (PDF). Alcohol Wellness and Research Earth. 21 (3): 247–253. PMC6826809. PMID 15706777. Archived (PDF) from the original on xv November 2010.

- ^ Bavolek, Stephen J.; Henderson, Hester L. (1990). "Child maltreatment and alcohol abuse: Comparisons and perspectives for treatment". In Potter, Ronald T.; Efron Patricia S. (eds.). Assailment, Family unit Violence and Chemical Dependency . Binghamton: Haworth Press. pp. 165–184. ISBN978-0-86656-964-iv.

- ^ Daro, Deborah; McCurdy, Karen (April 1991). Current Trends in Child Abuse Reporting and Fatalities: The Results of the 1990 Annual L Country Survey. Working Paper Number 808 (Report). Chicago, Illinois: National Committee for Prevention of Child Abuse. p. 34.

- ^ Cloninger, C. Robert; Sigvardsson, Sören; Bohman, Michael (1996). "Blazon I and Blazon II alcoholism: An update" (PDF). Booze Health & Research World. xx (1): 18–23. PMC6876531. PMID 31798167.

- ^ Sher, Kenneth J. (1991). Children of alcoholics . United States: University of Chicago Printing. ISBN978-0-226-75271-6. OCLC 23176799.

- ^ Sher, Kenneth J. (1991). "Affiliate 6: Psychological Characteristics". Children of alcoholics . United States: Academy of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-75271-6. OCLC 23176799.

- ^ Drejer, Kirsten; Theikjaard, Alice; Teasedale, Thomas W.; Schulsinger, Fini; Goodwin, Donald W. (November 1985). "A Prospective Report of Young Men at High Hazard for Alcoholism: Neuropsychological Assessment". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 9 (6): 498–502. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1985.tb05590.x. ISSN 1530-0277. PMID 3911808.

- ^ Gabrielli, W.F.; Mednic, S.A. (1983). "Intellectual performance in children of alcoholics". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 171 (vii): 444–447. doi:10.1097/00005053-198307000-00009. ISSN 1539-736X. PMID 6864203.

- ^ Schaefer, K.Due west.; Parsons, O.A.; Vohman, J.R. (July–August 1984). "Neuropsychological differences betwixt male familial and non-familial alcoholics and non-alcoholics". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 8 (4): 347–351. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1984.tb05678.x. PMID 6385756.

- ^ Tarter, Ralph Due east.; Hegedus, Andrea M.; Goldstein, Gerald; Shelly, Carolyn; Alterman, Arthur I. (March 1984). "Adolescent Sons of Alcoholics: Neuropsychological and Personality Characteristics". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 8 (2): 216–222. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1984.tb05842.ten. ISSN 1530-0277. PMID 6375434.

- ^ Wolin, South.J.; Bennett, L.A.; Noonan, D.L.; Teitelbaum Thou.A. (March 1980). "Disrupted family rituals: A factor in the intergenerational transmission of alcoholism". Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 41 (3): 199–214. doi:10.15288/jsa.1980.41.199. ISSN 0096-882X. PMID 7374140.

- ^ O'Farrell, T. J.; Fals-Stewart, Due west. (2003). "ALCOHOL ABUSE". Periodical of Marital and Family Therapy. 29 (1): 121–146. doi:x.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb00387.ten. PMID 12616803.

- ^ Bratek, Agnieszka; Beil, Julia; Banach, Monika; Jarząbek, Karolina; Krysta, Krzysztof (2013). "The Impact of Family Environs on the Development of Alcohol Dependence" (PDF). Psychiatria Danubina. 25 (Supplement 2): 74–77. PMID 23995149. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 Apr 2018. Retrieved 26 Apr 2018.

- ^ "The bear on on children". American Addiction Centers. Centers, American Addiction. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Kaur, D.; Ajinkya, South. (2014). "Psychological touch of adult alcoholism on spouses and children". Medical Periodical of Dr. D.Y. Patil Academy. vii (2): 124–7. doi:10.4103/0975-2870.126309.

- ^ Brown, Strega, Leslie, Susan (2015). Enquiry as Resistance: Revisiting Critical, Indigenous, and Anti-Oppressive Approaches. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press Inc. p. 5. ISBN978-1551308821.

- ^ a b c d Amodeo, Maryann; Griffin, Margaret; Paris, Ruth (2011). "Women's Reports of Negative, Neutral, and Positive Effects of Growing Upwardly With Alcoholic Parents". Families in Social club: The Journal of Gimmicky Social Services. 92 (ane): 69–76. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.4062. S2CID 143817928.

- ^ a b Werner, E Eastward (4 Jan 2015). "Resilient offspring of alcoholics: a longitudinal study from birth to age 18". Periodical of Studies on Booze. 47 (i): 34–40. doi:ten.15288/jsa.1986.47.34. PMID 3959559.

- ^ a b c Wright, Deborah M.; Heppner, P. Paul (1993). "Examining the well-being of nonclinical college students: Is knowledge of the presence of parental alcoholism useful?". Journal of Counseling Psychology. forty (3): 324–334. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.xl.3.324.

- ^ a b Moser, Richard P.; Jacob, Theodore (i January 1997). "Parent-child interactions and child outcomes as related to gender of alcoholic parent". Periodical of Substance Abuse. 9: 189–208. doi:x.1016/S0899-3289(97)90016-X. PMID 9494949.

- ^ a b c Harter, Stephanie Lewis (i April 2000). "Psychosocial adjustment of adult children of alcoholics: A review of the recent empirical literature". Clinical Psychology Review. 20 (3): 311–337. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00084-1. PMID 10779897.

- ^ Gandara, Patricia (16 May 1994). "Choosing Higher Teaching: Educationally Ambitious Chicanos and the Path to Social Mobility". Education Policy Assay Archives. 2: 8. doi:ten.14507/epaa.v2n8.1994. ISSN 1068-2341.

- ^ Jacobson, Sandra W (1997). "Assessing the Touch on of Maternal Drinking During and Later on Pregnancy" (PDF). Booze Health and Research World. 21 (three): 199–203. ISSN 0090-838X. PMC6826808. PMID 15706769. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2010. Retrieved nineteen July 2008.

- ^ a b Larkby, Cynthia; Mean solar day, Nancy (1997). "The Effects of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure" (PDF). Booze Health and Research World. 21 (three): 192–197. ISSN 0090-838X. PMC6826810. PMID 15706768. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alcoholism_in_family_systems